Biography published by Eva Bosch in January 2022

Eva Bosch

Eva Bosch is a Catalan painter, writer and video maker born in Barcelona. At present Eva lives and works in London with regular visits to her atelier in Malgrat de Mar (Barcelona), combining her studio work with lecturing in the History of Art.

“I grew up in Montmany-Figueró; a small village north of Barcelona where the novel novel “Els Sots Ferestecs” (Dark Vales), written in 1901 by Raimon Casellas takes place. This village has haunted me all my life and it has been a great source of inspiration for my work. This novel was translated from Catalan into English by Alan Yates in collaboration with me in 2014.

Catalan Modernism in literature, initiated by Casellas is unique and particular to Catalonia. It extended to architecture, music and painting. It was a source of inspiration in the work of Antoni Gaudí, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso or Salvador Dalí. My cultural background constantly nourishes my work. Cultural identity is to me the core of any form of universal Art. Joan Miró once said that he would like to be seen as an international Catalan; I would also like to be regarded in this way

Like my father, I have always had a wide range of interests. He had to be a polymath and a jack of all trades to support a large family during Franco´s Spain. I was privileged by comparison. Since my arrival to the United Kingdom in 1973, I benefited from several awards and scholarships provided by a generous, now long gone, British welfare state. I obtained an M.A in fine Art Painting at the Royal College of Art where I was granted an award to study at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. In 1995 I won the Pollock Krasner Award. I have had residencies in Italy, France, Spain,Taiwan and Turkey.”

In the last fifteen years I have researched prehistoric painting in Europe as well as in residencies in Senegal and Turkey. In Catalhöyük, a city in Anatolia dating from 9000 years ago, I worked next to archaeologists and scientists.

The study of prehistoric paintings has reinforced my belief that the urge of mark making does not change through millennia. The marks left behind by an individual portray a moment in time expressing an emotion or a need. What gives them value is the feeling they arouse which is universal, but like fingerprints is different for every viewer.

The post-modern world is saturated with highly sophisticated technology. As a result, the modern artist faces an immense challenge. The difficulty lies in holding on to one’s personal raft while sailing the ocean of possibilities and bringing to shore something alive.”

“Els Sots Feréstecs”

https://darkvales.wordpress.com/

by Raimon Casellas

About my work

The development of modern technology and the extraordinary new possibilities offered to image makers has created the need to look back to ancient art with the hope of finding clues to read with fresh eyes and follow up using new tools.

My interest in antiquity dates back to my early childhood in a mountain village. I grew up surrounded by Neolithic petroglyphs and Iberian settlements. The community’s religious rituals were a mixture of paganism and fundamentalist Christianity. The former was haunting, the latter disturbing but instructive.

My comprehensive art education included the RCA (Royal College of Art) after an intense year in Italy painting in a secluded village in the mountains. The richly descriptive approach and oneiric imagery I had picked up in England were cut loose in Amsterdam by the Puritanism of the Dutch School, leaving me reduced to my bare bones, so to speak, and ready to return home. There I started to paint fragmented imagery, perhaps as a means of moving away from figurative work that felt rhetorical and repetitive. I then tried to understand further the use of light via colour and my images became limited to amorphous – and sometimes geometrical – forms. This process was concluded a decade later in England where I started to use bitumen, wax, varnishes and similar materials as well as drips in order to draw, partly in response to the simplicity of a group of statuettes I saw at the British Museum, originally from Benin in Africa. The Benin imagery and African drums helped me take a more direct approach to drawing, paradoxically getting rid of frills by daring to include them in my painting.

During these recent years, due to a certain extent to my work as a teacher, research in art libraries has garnered me a large collection of images ranging from Palaeolithic paintings from caves and rocks in Spain to the Neolithic frescoes of Çatalhöyük in Turkey as well as those of a later date found in the excavated remains of the civilization that existed in Mohenjo Daro and Harappa in the Indus Valley, Pakistan. My fascination for such images is growing by the day.

My first live experience with iron oxide red paint on bare rock, free from glass screens in museums, was in 2008, in the Serra de Godall in Ulldecona, Spain. A composition of a group of images of humans and animals, mostly deer in full flight, dating from 6000-5000BC. Some figures are carrying bows and arrows and some animals appear to have been wounded, hence it could be a hunting scene. A passive figure with a long ponytail holding with both hands a stick like a broom between his/her legs is standing motionless on the left, observing the scene. This painting had a powerful effect on me.

During my first residency at a Neolithic settlement, Çatalhöyük (Turkey 2007), as part of an interdisciplinary team, I began to observe light entering the prehistoric units. My work led to a significant discovery: a sun clock (a beam of light manifested in each dwelling enters through an opening at the roof and drifts like a sundial to different areas inside each house. As artist in residence at another, older, Neolithic settlement Aşıklı Höyük, successive visits to the site (2015, 2017, 2019) have further developed my interest in observation of this phenomena and the formation of new work in new media. I have studied the journey of sunbeams travelling inside the 13 replica units built at Aşıklı Höyük, through drawing, photography and film. During my several visits I have discovered that because the egress of the unit is from the roof and placed at different cardinal directions, the angle of the beam of light differs in each unit. In 2019, I invited some colleagues of mine to visit Aşıklı Höyük with the aim of developing a dialogue with others through creative responses, observations and interpretations of the settlement, in dialogue with Prof. Mihriban Ozbasaran, Director of the Aşıklı Höyük Project and her team. This specific dialogue between expert practitioners in art, archaeology, and science in this unique context will open up new discussions, and perhaps further inspire other artists to pursue new avenues combining art and science.

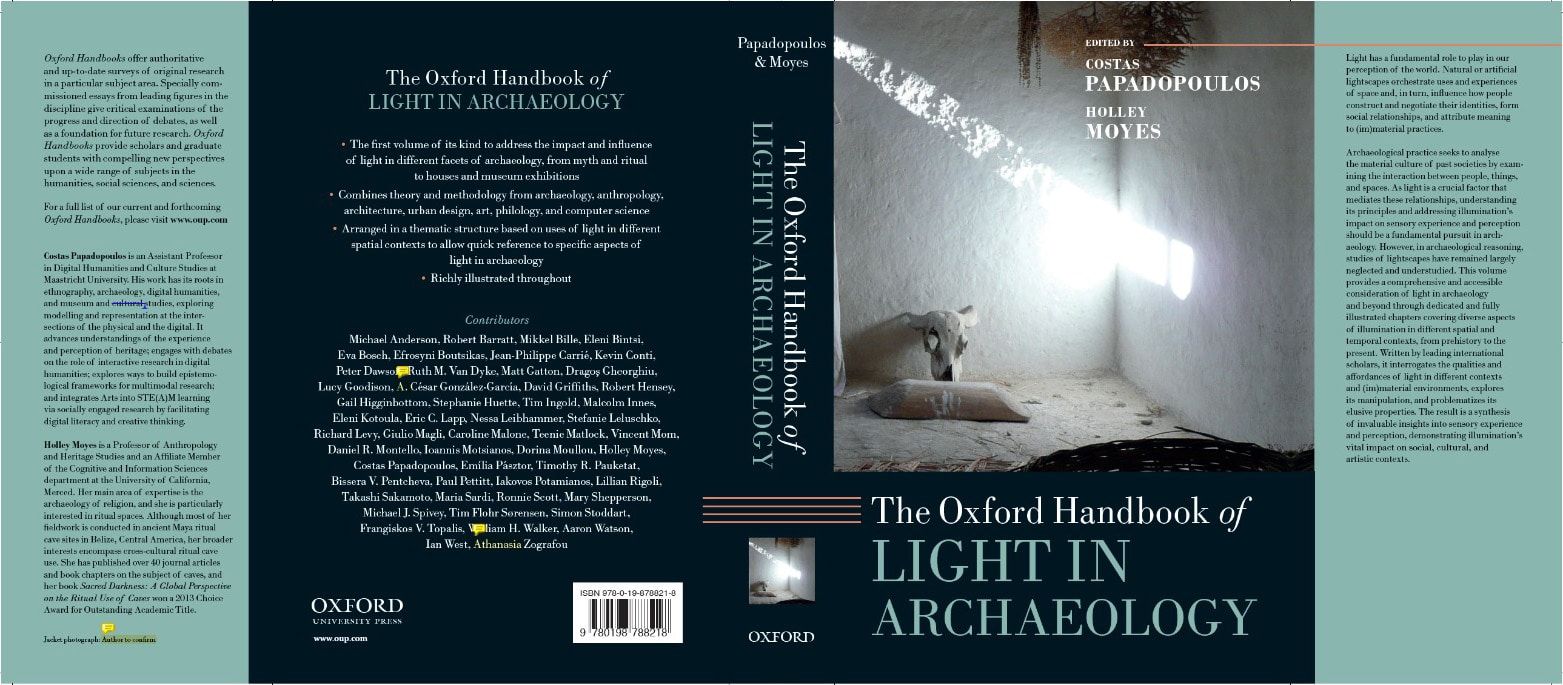

The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology

In 2010 I took part in the conference hosted in Bristol called Tag 2010-Bristol which led to a collaboration with archaeologist Costas Papadopoulos for his book titled “The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology, due to come out February 2022. The chapter i wrote for the book is called “Çatalhöyük a study of light and darkness”

The Oxford Handbook of Light in Archaeology – cover photograph by Eva Bosch

Africa Hombre Cerilla

Commentary on Eva Bosch by Matthew Tree

Anglo-Catalan writer living and working in Barcelona.

It would be just too easy, too cosy, too convenient, to claim that Eva Bosch’s work, especially over the last few years, has been influenced principally by that of her fellow Catalans Salvador Dalí (the dreamlike quality), Joan Miró (the quirky, unpredictable shapes) or Antoni Tàpies (the use of collage effect and diverse materials).

Certainly these influences, some conscious, others less so, are present in many of her paintings, but when you look at these more carefully it becomes clear that Bosch has delved into many other potential sources of inspiration, which, unlike the three artists mentioned above, are far removed from her in time and often in place as well.

Some of her titles (‘Africa Drawing’, ‘Africa Hombre Cerilla’) give the game away from the start: her true concern is with the primitive, but in the sense of ‘original’, ‘primary’, or ‘not derived’ (the definitions are from Webster), and not the more commonly used one of ‘crude’ or ‘rudimentary’.

Her acknowledged fascination with cave art, African art, and the art of the ancient cities of Asia Minor is not, for her, a simple question of aesthetics.

It is the excitement of contact with the earliest known attempts to depict the physical world, which still retain their capacity to astound, which still hint at their original magical intentions. This excitement, profoundly felt, is at the heart of the very best of Eva Bosch’s work, recreating as it does the sense of wonder that emanates from the finest ‘primitive’ painting.

Her work, then, complies with that condition which William Burroughs claimed was essential for any art which deserves the name: it has to ‘make things happen’ as he put it, that is to reach out to the onlooker and eliminate his or her initial inertia and indifference. Eva Bosch’s live and astonishing paintings do precisely that.